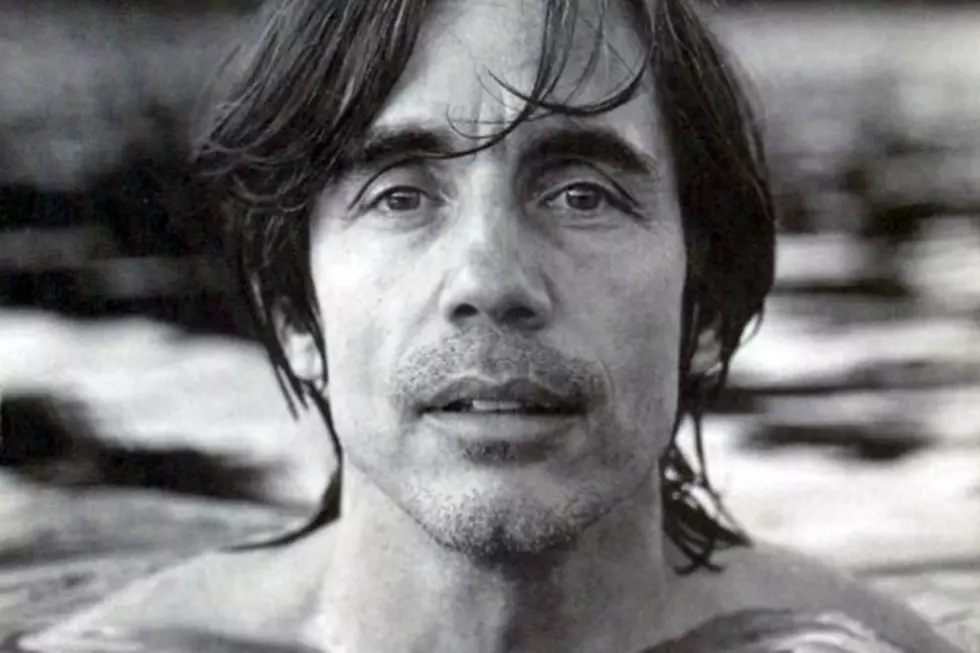

The History of Jackson Browne’s ‘World in Motion’

"There's a danger in seeming too serious," acknowledged Jackson Browne in the weeks following the release of his ninth album, 1989's World in Motion. "There's a danger that you can repel a large amount of people you want to reach."

It's a danger with which Browne was well-acquainted. After rising to prominence as one of the smartest and most tuneful singer-songwriters of the '70s, he'd drifted away from the eloquently phrased personal concerns that dominated his earlier records and started training his focus on political matters -- much to the chagrin of critics and fans who felt that he'd sacrificed the most compelling element of his artistry in order to deliver a message. And while few of Browne's fans would have argued the importance of the issues that motivated him, it was hard not to miss the universal themes and stark simplicity of his classic recordings.

As he later explained, the reasons for this change were largely a matter of personal evolution. "I think partly it's just because as you grow older, your personal questions are resolved and you begin to notice the world, and pay more attention to what's going on. I also started out with a first-person narrative style and wrote about my own life as if it were anyone's life -- and it is, in so many ways -- but after so many years, you're a famous person whose life has been commented on, and people mistake what you're writing as if it's about a specific life."

The political climate of the '80s also played a large part. "I write fewer [personal songs] because I'm less interested," he continued. "I was politicized by the Reagan era. I was political in matters of ecology during the '70s, and a critic of the Carter approach, because he sort of went back on things. I don't think anyone knew to what extent Reagan's policies would alter the landscape, and I was politicized by that. Things that were bad got worse, and I was affected by that [...] I was very deeply moved by going to Central America."

Browne's broadening lyrical focus coincided with a change in sound. In fact, even before releasing politically themed albums like 1986's Lives in the Balance, he'd begun moving away from the acoustic guitars and pianos that anchored his earlier efforts, shifting to a more produced approach that relied more heavily on electric guitars and synthesizers. While mid-'80s singles like "In the Shape of a Heart" boasted more of a radio-friendly sheen than they might otherwise have enjoyed, they were also a good deal more cluttered than the songs that made him famous -- and they took quite a bit more to assemble, both in terms of time as well as studio personnel.

By the time he entered the home stretch with World in Motion, Browne was three years removed from Lives in the Balance, and had he'd spend a significant portion of that time recording -- and re-recording -- the set of songs that would eventually arrive in stores on June 6, 1989. Co-producing alongside future Heartbreaker Scott Thurston, Browne employed a long list of personnel that included session ringers like percussionist Alex Acuna and bassist Bob Glaub as well as famous friends such as David Crosby and Bonnie Raitt. As the overdubs piled on, the songs grew slicker, and although the resulting record is clearly cut from the same fabric woven through Browne's earlier efforts, it's padded with an identifiably '80s gloss.

It had a distancing effect for critics, who greeted World in Motion with some of the least enthusiastic reviews of his career -- and for fans, as evidenced by the record's No. 45 peak on the Billboard album chart, as well as its failure (the first in Browne's distinguished career) to achieve gold or platinum certification. While there was certainly room for politically themed rock on the pop charts -- Don Henley hit paydirt with the Reagan-excoriating The End of the Innocence that same year -- but while World may have been admirably earnest, it didn't hit home the same way.

That earnestness may have ended up getting in the way of the clear-eyed songwriting that fueled Browne's classic work. "You have to have some hope that things can change, or else you have no power," he argued in a discussion of his late '80s work. "After so many years of doing concerts and performing and being places that not everybody gets to go, it would be silly for me to not recognize that I am, to some degree, a pop star," he mused. "I have certain privileges because of it, but I don't think of myself in those terms. I dress simply. Really, I think of myself as a songwriter."

Listen to 'Enough of the Night'

"He wasn't as overtly political in conversation," insisted one person present during the sessions during a conversation with Ultimate Classic Rock. "It was still second to 'How do we make this sound good and be good?' We even had a joke -- I think we used to call the political songs 'the little speeches.' But he wasn't constantly pounding the console about politics. All the hand-wringing was about the record-making."

Hand-wringing in pursuit of artistic excellence is a noble endeavor. But it gets tricky when the artist isn't operating in an environment that allows for an open exchange of ideas, and at this point, Browne had acquired enough clout to be able to punch his own card with his longtime label, Elektra Records. With his own studio, a contract that afforded him large advances, and a legacy that loomed over all of his subsequent efforts, he was free to refine his recordings endlessly without much in the way of meaningful feedback. As our source explained, "He was completely self-contained."

But ultimately, that containment may not have been as problematic as the weight of expectations -- whether fans' or his own. "He thought he had to interpret himself as a rock star," continued the World in Motion session insider, explaining Browne's decision to beef up the simplicity of his earlier records with more production. "An arena-level rock star doesn't just strum a guitar and sing quietly to himself and let the whole world listen in, you know? That isn't what they do. They write large on a giant canvas and they broadcast their intentions loudly."

If anything, Browne got quieter in the years after World in Motion, entering a four-year recording hiatus before re-emerging with his next record, 1993's I'm Alive. And while that album's liner notes included just as many names as his previous effort, its sound was a lot more natural -- and the songs signaled what ultimately proved to be a return to the inward focus that resonated with fans, although he cautioned listeners not to read too much into confessional-sounding lyrics.

"The whole reason I write songs is to confront what’s going on inside me. I just came in touch with the most fundamental reasons for writing a song, and that kept me going," he told the Chicago Tribune after its release. "I hope these songs have value to other people. To me, half of each song I write exists in the listener. I wouldn’t want to endanger that by making them so specifically about me."

See Jackson Browne and Other Rockers in the Top 100 Albums of the '70s

More From 1073 Popcrush